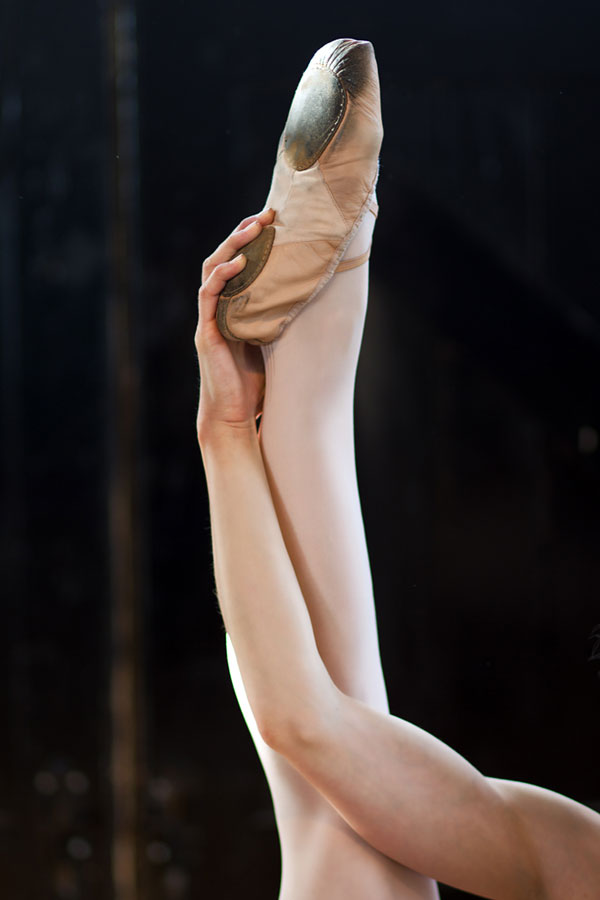

When I took up ballet as an adult and as a beginner there was a common protest from my friends:

You’ll wreck your body.

Ballet has developed a reputation, deserved or otherwise, of being an injury-prone activity. We accept this blindly without taking into account who is being injured and how.

A recent article in Melbourne’s Herald Sun, barely more than 100 words in length, carried the headline “Ballet hazards high.”

The headline alone invites justification of pre-determined perceptions of ballet.

“New research from Sports Medicine Australia has found young dancers are at a higher risk of injury than other athletes, with 75 per cent risk.”

That’s a worrying statistic – but read on.

In a quote from the study’s researcher, Monash University’s Christina Ekegren, we learn more about the who, rather than the what, they were studying,

“We found that the majority of the dancers monitored danced six days per week, with each participant dancing an average of 30 hours per week.

This was on top of their normal school work.”

The sample is a very specific demographic.

In fact, as Christina Ekegren tells the ABC, the dancers they looked at were between the ages of 16 and 18 years of age and were at a pre-professional level of dance; studying at the Royal Ballet School, the Central School of Ballet or the English National Ballet School.

When asked if her findings could be extrapolated to the adult beginner demographic, Christina Ekegren says no.

“Í don’t think my results could be generalised to the population you’re interested in,” she explains. “many of the dancers’ injuries were the result of overuse due to high training loads.”

As previously mentioned, the dancers are aspiring professionals who were dancing an average of 30 hours per week and doing school work on top of that. Christina Ekegren also notes to the ABC that there are also potentially getting less sleep than necessary.

“Relative to the number of hours that they’re dancing, the injury rate is actually quite low,” she says. ” The activity itself is quite low risk but what makes it high risk is the fact that they’re dancing for so many hours.”

When it comes to adult beginner ballet classes taken for fun, fitness or even fashion, it would be the exception to dance more than a few hours per week. If you were to dance every ballet class at my studio, you’d only be dancing five and a half hours per week.

Yes, injuries are possible in any physical activity – whether from poor technique, lack of warm up, exerting yourself beyond your capability, or otherwise.

Netball, one of the most popular sports in Australia can lead to broken fingers and even has an injury with its name on it: netball knee.

Likewise, tennis elbow. But would your friends show concern for your new-found interest in tennis or netball?

Pre-existing concerns about ballet-related injuries generally assume a professional, or a pre-professional dancer, but when taking into account sensible measures, there’s no reason adult beginner ballet should be particularly dangerous.

If you select a studio that uses qualified teachers, follow the instructions given and dance to your own level, then there is no reason to fear embracing a new pastime.

This post was originally published here.

of the knee or knees. This

of the knee or knees. This